The longer I write, the more I’m intrigued by how a word can conceal as much if not far more than it reveals. Yet if regarded with care, any word can serve not as a wall but as a window to what it can’t further express.

One of my favorite books is The Hundred Greatest Stars, by the astronomer James B. Kaler, because he transforms the word “star” from a single encompassing category into something like a prism reflecting the light of a dizzying variety of stellar objects.

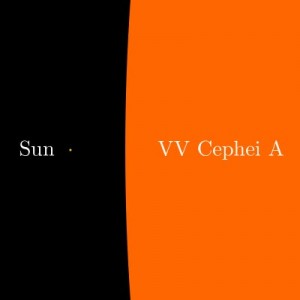

T ake, for instance, the star V V Cephei. This red supergiant, a mere 2,000 light years away, is so large that its diameter is almost the size of the orbit of Saturn. How big is that? Well, take a look at this humbling comparison with our own star, the sun.

ake, for instance, the star V V Cephei. This red supergiant, a mere 2,000 light years away, is so large that its diameter is almost the size of the orbit of Saturn. How big is that? Well, take a look at this humbling comparison with our own star, the sun.

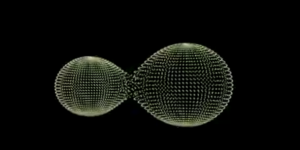

Another star, W Ursae Majoris, is an even closer neighbor, only 160 light years away, which places it practically right across the street from us in the galactic neighborhood. This is a double-star system, though with a doozy of a twist—the two stars are so close together that they actually touch as they whirl around each other, forming, in essence, a strange revolving single object.

Kaler’s book is filled with white dwarf stars; double, triple and even four-star systems;  neutron star x-ray bursters; super magnetic stars; a whole panoply of cosmic difference. After reading his book, I’ve found it impossible to peer up at the night sky and see those scattered grains of light as anything resembling a uniform category. The word “star” now offers the infinite possibilities of the universe itself.

neutron star x-ray bursters; super magnetic stars; a whole panoply of cosmic difference. After reading his book, I’ve found it impossible to peer up at the night sky and see those scattered grains of light as anything resembling a uniform category. The word “star” now offers the infinite possibilities of the universe itself.

Our universe is a big place, though, so why not take a look at a word that operates on a more intimate level? A smile is among the most common of human expressions, one that cuts across all cultures. Yet the word “smile” implies a singular form that it is not and can never be. As Daniel McNeill observes in his book The Face, smiles “vary like a kaleidoscope. Turn the tube slightly, change a nuance here or there, and a new meaning arises.” Some languages are better at expressing this morphing quality than others. In Japanese, several words take on this challenge: “niko-niko, a smile of peacefulness and content; nita-nita, a smile tinged with contempt; ni, a brief grin; niya-niya, an often unpleasant way of smiling when suppressing joy; ninmari, a smile after achieving a goal; chohshoh, a sneer.”

The task of a writer, it seems to me, is recognizing that any word will take you only so far, that its core definition is simply a first step. Without this understanding, words can actually restrict your vision of the world.

As a teacher, I’ve become weary of the words “beginning” and “ending,” which I feel limit my students’ attempts to learn how to shape a story. Sometimes a young writer’s story will first feature reams of exposition, backstory upon backstory before a scene finally offers the drama we crave, all in the service of “beginning” the story in some chronological fashion. And sometimes that same hypothetical young writer will “end” a story with a flourish that implies, well, that’s that!

Yet there can be no “beginning” to any story, because there will always be a series of events that have come before. And, as for an “ending,” the world simply continues on its way, regardless of our attempts at closure, doesn’t it?

So, I ask my students to think of their first page as the point of entry into an already unfolding narrative, and to think of the last page as their point of departure from that same continuing narrative. Charles Dickinson’s hypnotic short story “Risk” may take place entirely during a single evening while a circle of friends and acquaintances play a game of Risk, but its most central drama concerns the loss of a child that occurred one year earlier. On the other hand, Graham Swift’s story “Learning to Swim,” though it takes place within an afternoon’s half hour at the beach, dramatizes the moment when a child makes his choice of navigation between his two warring parents, a choice that will, the reader assumes, set the structure of the family for many years to come.

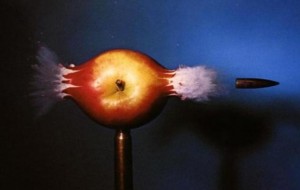

Where you enter a narrative and where you exit gives you the shape of the fiction you are trying to call into being. Or, to put it more bluntly, the bullet may be the wider world of your narrative flying along, but the apple is your story.