More years ago than I like to count, when I was but a first-year graduate student in creative writing, I came upon a slim volume in a bookstore titled Shakespearean Design, by Mark Rose. I pulled it off the shelf and gave it a glance, because I was taking a summer literature course on the Bard and soon found myself deep in a book that would influence me as a writer for the rest of my life.

Not many people know this, but Shakespeare never divided a single play into five acts. As Mark Rose notes, “In Shakespeare’s lifetime not one of his plays was published with any division of any kind.” And yet all his plays, as we know them today, go hummingly about their business from Curtain Rise and Act One on through to Act Five and Curtain Close. These divisions were added to the plays many years after Shakespeare’s death.

So if our greatest playwright never tinkered with five acts (or any acts), what sort of structure did he use to shape his narratives—surely he didn’t simply scribble away?

He was influenced by late medieval and early Renaissance diptych and triptych paintings. Think of Hieronymus Bosch’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony, as an example of a triptych. While the individual paintings can stand alone, they are given greater meaning and context when seen as part of a series.

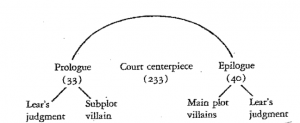

In his plays, Shakespeare used the diptych and triptych as his basic units of structure. Here’s a diagram Mark Rose has worked up for the opening of King Lear. Here’s a classic triptych structure, with the brief prologue and epilogue framing a much larger scene in the middle. Notice how the first and third scenes have very nearly the same number of lines, creating an elegant symmetry, while their very briefness is juxtaposed with the large court scene, the one where Lear has a fit and divides his kingdom. Also, the prologue and epilogue are private scenes, where characters gossip or conspire, in contrast to the grand public spectacle of the middle scene.

In his plays, Shakespeare used the diptych and triptych as his basic units of structure. Here’s a diagram Mark Rose has worked up for the opening of King Lear. Here’s a classic triptych structure, with the brief prologue and epilogue framing a much larger scene in the middle. Notice how the first and third scenes have very nearly the same number of lines, creating an elegant symmetry, while their very briefness is juxtaposed with the large court scene, the one where Lear has a fit and divides his kingdom. Also, the prologue and epilogue are private scenes, where characters gossip or conspire, in contrast to the grand public spectacle of the middle scene.

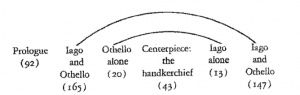

Shakespeare was never one for cookie-cutter regularity and was more than capable of interesting change-ups when it came to framing scenes. This next  diagram is from Othello. Here, Shakespeare uses an arch form to shape the narrative, two framing diptychs that surround a central scene. Again, notice the elegance of how the paired scenes (Iago and Othello; Othello alone/Iago alone) are nearly the same length. It’s the center scene, Iago’s discovery of the handkerchief, which sets off the drama, the single act around which these two characters’ fates will revolve.

diagram is from Othello. Here, Shakespeare uses an arch form to shape the narrative, two framing diptychs that surround a central scene. Again, notice the elegance of how the paired scenes (Iago and Othello; Othello alone/Iago alone) are nearly the same length. It’s the center scene, Iago’s discovery of the handkerchief, which sets off the drama, the single act around which these two characters’ fates will revolve.

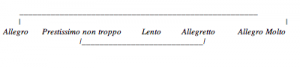

Rose’s beautifully written analysis is filled with smart diagrams like the two above. Reading through the book, one gets a sense of the infinite possibilities of structure, how manipulating the placement of small units can lead to a greater whole. Once you’re clued into these Lego-like building principles, you can find them in many different art forms. The Fourth String Quartet by the 20th-century composer Bela Bartok, for example, has a structure nearly identical to the opening of Othello:

Othello:

The first and fifth movements share musical themes and material, as do the second and fourth movements, and the middle movement stands apart, its eerie musical material particular to itself. One could see this as a kind of rhyme scheme: ABCBA.

This arch form was an influence on the structure of my second book, The Art of The Knock, though I built mine out of seven sections. David Mitchell’s magisterial Cloud Atlas employs a grand version of the arch structure, which can be read as ABCDE F EDCBA—an arch, but also an elaborate triptych.

We structure our fictions, and we also structure our memories. Sven Birkerts, in his marvelous book The Art of Time in Memoir, describes the “time frame” of Geoffrey Wolff’s The Duke of Deception. Wolff begins his memoir with the sudden announcement by phone, as he’s vacationing in Narragansett, of his father’s death, then employs the bulk of the book to tell the narrative of his life with his father, and then ends with a return to the site of Narragansett. Another triptych.

Yet must structure always aspire to symmetry? Yann Martel’s first novel, Self, serves as an effective counter-argument. The novel is comprised of only two chapters. The first is 329 pages long. Chapter two is a single page. It’s hard to imagine a more lopsided diptych than this, but that final second chapter more than holds its own with its bulkier companion.

Did any of these writers have their structure set in mind from the beginning? Maybe. I like to think, though, that these various shapings come about through the writing. If conceived of too soon, a structural plan could easily turn constricting. But if an architecture arises from the thicket of writing’s multiple discoveries, then it gives shape to what might otherwise remain amorphous.