After my last post, on the units of structure Shakespeare employed in his plays, scenes arranged as diptychs and triptychs, I thought I’d continue my thoughts on structure in writing by quoting a prose poem by the poet David Ignatow, titled “The Life They Lead”:

I wonder whether two trees standing side by side really need each other. How then do they spring up so close together? Look how their branches touch and sway in each other’s path. Notice how at the very top, though, they keep the space between them clear, which is to say that each still does its thinking but there is the sun that warms them together.

“Do their roots entangle down there? Do they compete for nourishment in that fixed space they have to share between them, and if so, is it reflected in their stance towards one another, both standing straight and tall, touching only with their branches? Neither tree leans towards or away from the other. It could be a social device to keep decorum between them in public. Perhaps their culture requires it and perhaps also this touching of branches is to further deceive their friends and associates as to the relationship between them—while what goes on beneath the surface is dreadful, indeed, roots gnarled and twisted or cut off from their source by the other and shrunken into lifelessness, with new roots flung out desperately in a direction from the entanglement, seeking their own private, independent sources. As these two trees stand together, they present to the eye a picture of benign harmony, and that may be so, with both dedicated to the life they lead.

What does this have to do with structure? This prose poem offers us visually two trees, standing side by side in a symmetrical arrangement, the view we have of trees day by day. But there is another symmetry, a secret diptych: the branching system above ground is echoed by the branching root system below ground. The two systems roughly mirror each other, and it is instructive to remember that every tree we see as we go about our daily lives is really only half that tree.

So, we have the benign pairing of trees above ground, the more fearful symmetry of the trees below ground, their roots competing for sustenance. Two seemingly peaceful and yet warring trees can of course be seen as a statement on the tug and pull of human relationships, on how psychological tension balances collaboration. But this seems to me to also be a good model for structure. Writers try to build, through chapters, stanzas, and sections of a short story or essay (every imaginable variation on Frost’s tennis net, really), something of tensile strength that will hold a work of the imagination together. But because it is a work of imagination, such an endeavor is not so simple. Held within the parts we fit together is a world of human ambiguity and conflict, a root system of potential chaos and entropy. The tension between the two is the life we learn to lead as writers.

We all know how messy writing can be, how guessing and chance, in addition to simple due diligence through an intractable problem, get us to where we need to go. But through the mess of creation, structure somehow does get its say. Just as, in Ignatow’s prose poem, those chaotic, competing roots below the surface eventually grow a graceful tree. Patterns do begin to emerge. Yet the structures you choose should be as individual as your own creative vision. I’d like to emphasize this point by turning to our little friends, the ants.

There’s a myrmecologist named Walter Tschinkel of the University of Florida who has developed a peculiar specialty: He pours a gooey mixture that resembles dental plaster into ant nests; when the mixture fills all the passageways of the nest and then hardens, he digs away the surrounding dirt and is left with the architecture of the ant colony. It’s an ingenious way to study the structure of ant societies, though perhaps we shouldn’t dwell too much on all those drowned ants preserved within his plaster-like pastes. What Tschinkel discovered is that every ant species builds a different-shaped nest.

They each have “a specific nest design, and each builds from a particular set of rules,” as Jack McClintock states in a Discover magazine article. A particular set of rules that build a specific design . . . sou nds a lot like Shakespeare’s manipulation of scenes into combinations of diptychs and triptychs.

nds a lot like Shakespeare’s manipulation of scenes into combinations of diptychs and triptychs.

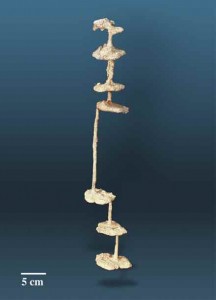

Each ant colony is a formal, planned shape, built to contain the teeming life within. This ant nest on the left resembles an underground tornado, a seeming chaos of design slimming down to a narrow base.

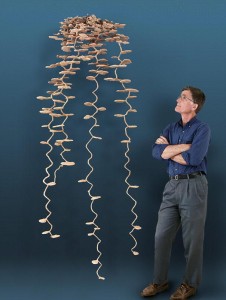

This nest on the right, in contrast, resembles a far more staid series of steps going down.

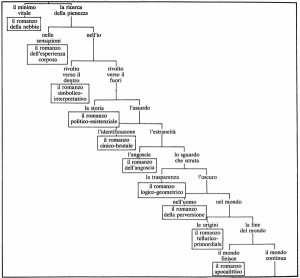

This last nest reminds me of the chart Italo Calvino worked up for his novel If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler—but only after he had written the book.

All structure leans toward elegance, I believe, even when it might at first seem a little lop-sided. Examining closely a book’s architecture will reveal much of its meaning as well. One example is the structure of Yann Martel’s first novel, Self, which I mentioned in my previous post. Another example is the story collection A Song for Nettie Johnson, by Gloria Sawai (winner of Canada’s Governor General’s Literary Award), which is dominated by the novella-length title story (and by the way, how can anyone not love a book that ends with a story titled “The Day I Sat with Jesus on the Sundeck and a Wind Came Up and Blew My Kimono Open and He Saw My Breasts”).

Sawai’s novella that begins the collection (and clocking in at ninety pages it’s nearly a third of the entire book) is a tale of two damaged people who somehow manage to create a working relationship, as if their two separate internal limps balance each other out (two trees, anyone?). Religion and art and the imagination also figure largely in this title story, and it seems as if Sawai at first sets forth the grand themes of her work in this novella so that the eight shorter stories that follow become variations, as if we’ve left the larger lake and are now making our way through the winding tributaries.

We build our books in much the way different species of ants construct their underground homes, with an astonishing variety of invention. And so the shape of our stories and poems and essays become personal mirrors that reflect our secret selves.