“To see is to have seen,” said the great 20th-century Portuguese poet, Fernando Pessoa. This seemingly simple sentence can be read more than one way. First, as a critique: we see mainly what we have already seen, that sight is a well-worn habit. Another interpretation suggests the opposite: that at its best, sight is a form of understanding, arrived at only if we have truly seen through life’s visual static. Both interpretations, I think, are true, each the flip of the other.

Tho ugh for most of his adult life, Pessoa lived solely in the city of Lisbon, rarely venturing outside its borders—he was a poet of inner travel. In his writing, he invented a series of alter egos—personalities he called “heteronyms” (as opposed to mere pseudonyms)—and he gave his three main creations names—Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis, Álvaro de Campos—along with past histories, astrological charts, physical features and their own signatures. Most of all, each heteronym was a different poet, and each wrote a different poetry from the others.

ugh for most of his adult life, Pessoa lived solely in the city of Lisbon, rarely venturing outside its borders—he was a poet of inner travel. In his writing, he invented a series of alter egos—personalities he called “heteronyms” (as opposed to mere pseudonyms)—and he gave his three main creations names—Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis, Álvaro de Campos—along with past histories, astrological charts, physical features and their own signatures. Most of all, each heteronym was a different poet, and each wrote a different poetry from the others.

Pessoa created out of his own conflicting inner voices a literary salon. Their leader (and the first to be created) was Alberto Caeiro, a poet of nature and clarity of vision. The identity and poetry of Caeiro came to Pessoa in a flash one day in March 1914, and over the next three days he wrote (transcribed?) Caeiro’s masterpiece, a book titled The Keeper of Sheep. This book had a particular vision that influenced—by their own admission—the work of the other heteronyms. For me, that vision is perhaps best summed up in the 45th poem in that collection.

A row of trees in the distance, toward the slope . . .

But what is a row of trees? There are just trees.

“Row” and the plural “trees” are names, not things.

Unhappy human beings, who put everything in order,

Draw lines from thing to thing,

Place labels with names on absolutely real trees,

And plot parallels of latitude and longitude

On the innocent earth itself, which is so much greener

And full

Of flowers!

(translation by Richard Zenith, in Fernando Pessoa & Co.)

After reading this poem, I find that it affects the way I look at a tree, or any natural phenomenon, and how each tree or bush or flower is its one distinct self, which is obscured by mental and visual static when we add an abstraction to its description. Language can cast invisible expectations on what we think we simply see, as if seeing were simple! I thought I knew what a tree looked like.

Pessoa’s poem took me someplace I might never have otherwise arrived at. The best writing, whether non-fiction, fiction or poetry, is potentially a type of travel writing, and a reader experiences a complex imaginative work as a form of travel. Every work of literature should offer a journey, the challenge of an interior mapping that might lead a reader to him or herself. Writing that travels is the literature of any reader’s need for an inner journey.

Travel isn’t simply a geographical exercise. A journey into the land of adolescence, for example, is perhaps the loneliest type of travel there is, as we leave behind the carapace of our childhood and molt into the fraught emotional territory of adulthood. The entry into parenthood can be as shocking and bracing a form of travel as can be imagined. So, too, is the slow arch of committed negotiation that is the travel of marriage, or any long-term relationship, the intricate balance of one partner’s love with the other’s. The acceptance of one’s sexual orientation or identity is another form of travel, from one state of personal understanding to another.

My favorite city in the world is Lisbon. It’s a marvelous town to wander, especially with its winding streets and distinctive neighborhoods, nestled among many hills. Throughout the city, you will come upon what is known as a miradouro (“golden view”), a small park or plaza on an urban ridge overlooking the vast expanse of Lisbon, each one a new perspective on a city whose beauty keeps changing.

These vistas remind me of places I’ve been in my reading life that expanded my perspective, that helped me to see anew what I thought I had already seen or thought I understood. What follows here is a small collection of miradouros I’ve come upon in some of my favorite books.

In the novel Sacred Country by the British writer Rose Tremain, it’s 1952, and six-year-old Mary Ward is standing in the snowy yard outside her home with her family—mother, father, brother. They are participating in a nationwide, two-minute pause of silence, out of respect for the recently deceased King George VI. One immediately gets the sense that this is a family unaccustomed to silence. In fact, we get the sense that some of these characters are screaming inside. Mary, however, manages to find her place within this imposed silence, and it changes her life:

She tried another prayer for the king, but the words blew away like paper. She wiped the sleet from her glasses with the back of her mittened hand. She stared at her family, took them in, one, two, three of them, quiet at last but not as still as they were meant to be, not like the plumed men guarding the king’s coffin, not like bulrushes in a lake. And then, hearing the familiar screech of her guinea fowl coming from near the farmhouse, she thought, I have some news for you, Marguerite, I have a secret to tell you, dear, and this is it: I am not Mary. That is a mistake. I am not a girl. I’m a boy.

This is how and when it began, the long journey of Mary Ward.

So, too, begins Tremain’s novel, in which Mary slowly forges herself into Martin, the person she knows herself to truly be. A sacred country, Tremain tells us, is where one’s singular soul lives, and at times it can be a harrowing journey to find it, and sometimes an equally difficult journey to accept it.

“Lost Letters,” the first chapter in Milan Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, tells the story of Mirek, a dissident Czech essayist who became a well-known personality during his country’s Prague Spring. However, after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Mirek is in danger of being arrested. He should be disposing of his writings and communications with other dissidents before the police finally take it upon themselves to search his apartment, but first he feels he must retrieve the passionate letters he wrote years ago to his first lover, Zdena.

The first section of “Lost Letters,” however, has nothing to do with Mirek and those letters; instead, it opens with an ironic historical footnote:

In February 1948, Communist leader Klement Gottwald stepped out on the balcony of a Baroque palace to address the hundreds of thousands of his fellow citizens packed into Old Town Square. It was a crucial moment in Czech history—a fateful moment of the kind that occurs once or twice in a millennium.

Gottwald was flanked by his comrades, with Clementis standing next to him. There were snow flurries, it was cold, and Gottwald was bareheaded. The solicitous Clementis took off his own fur cap and set it on Gottwald’s head.

The Party propaganda section put out hundreds of thousands of copies of a photograph of that balcony with Gottwald, a fur cap on his head and comrades at his side, speaking to the nation. On that balcony the history of Communist Czechoslovakia was born. Every child knew the photograph from posters, schoolbooks, and museums.

Four years later Clementis was charged with treason and hanged. The propaganda section immediately airbrushed him out of history and, obviously, out of all the photographs as well. Ever since, Gottwald has stood on that balcony alone. Where Clementis once stood, there is only bare palace wall. All that remains of Clementis is the cap on Gottwald’s head.

This opening section haunts the rest of the chapter, reminding us as we follow Mirek, a dissident opposed to a regime that is attempting to erase the memory of the freedoms of the Prague Spring, that he himself is on a journey of erasure. Foolishly, he wants those letters back because he is ashamed that Zdena was ugly, and that he was once in love with her, a fact of his life that undermines the playboy cavortings of a popular dissident he has until recently been enjoying. Mirek, we come to understand, is no different in this sense from the government he opposes. The impulses, evasions and oppressions of governments are little different, except in scale, of the same characteristics of individual citizens—a lesson that continues to inform my understanding of politics. But there’s also a much more personal lesson to be learned here, that as we, as individuals, move through time further from our former, younger selves, how tempting it can be to alter our memories so that they better fit with the assumptions of our present selves.

Another of my miradouros concerns itself with memory. Here is the opening of “Cousins,” from a memoir by Jo Ann Beard, The Boys of My Youth:

Here is a scene. Two sisters are fishing together in a flat-bottomed boat on an olive green lake. They sit slumped like men, facing in opposite directions, drinking coffee out of a metal-sided thermos, smoking intently. Without their lipstick, they look strangely weary, and passive. They both have a touch of morning sickness but neither is admitting it. Instead, they watch their bobbers and argue about worms versus minnows.

My cousin and I are floating in separate, saline oceans. I’m the size of a cocktail shrimp and she’s the size of a man’s thumb. My mother is the one on the left, wearing baggy gabardine trousers and a man’s shirt. My cousin’s mother is wearing blue jeans, cuffed at the bottom, and a cotton blouse printed with wild cowboys roping steers. Their voices carry, as usual, but at this point we can’t hear them.

All right, let’s first address the obvious. If this is a memoir, then how in the world can Beard offer these details, since at the time of the scene she was a fetus? A lot of opinions are out there about whether Beard’s book is a work of fiction or nonfiction, and it has been categorized as both over the years. Me, I have no problem with reading this scene as nonfiction. Beard is imagining a scene that very well could have happened—she knows her mother and aunt well enough to evoke what they like to wear, like to do, and even how they would both try to gloss over morning sickness. And in this scene, she can see the beginnings of her complex relationship with her cousin.

This audacious opening to Beard’s essay declares, without having to say a word about it, that imagining is indeed part of our nonfictional lives. We imagine and fantasize all the time, every day, and why shouldn’t this be a part of the nonfiction we write? The miradouro of Beard’s two opening paragraphs widens the view of the genre, declaring that the fictions we create of our inner lives, and of our pasts, is nonfiction territory worth traveling.

The Galley Slave, a picaresque novel by the Slovenian writer Drago Jankar, offers another miradouro. It tells the story of the wanderings of Johan Ot through a Slovenian landscape set in the late Middle Ages. Early in the novel, Ot arrives in a middle-sized town and settles down, though everyone suspects he must be on the lam from something. Every small peculiarity of his is noted with suspicion. Eventually, he finds himself before a tribunal of the Inquisition, facing outlandish charges that at first amuse him, until various methods of persuasion encourage him to change his tune. Having fully “confessed,” he’s condemned to death by burning at the stake. As he is driven in a cart through the streets on his way to the awaiting pyramid of sticks and branches, a crowd gathers:

A thro ng of respectable folk who were simply unable and, more to the point, unwilling to tame their rage and hatred was crowding around the cart. And why not? Why shouldn’t they spit and flail at this man who had, after all, been proven guilty? Silently and with downcast eyes he endured the people’s righteous anger. He was guilty of everything they had proven, and probably quite a bit more. Directly or indirectly, he had inflicted some evil on each of those good, hard-working people. He had caused the death of this one’s livestock and that one’s child. Another was sick because of him, and yet another was tormented by vile monsters in his sleep. He had afflicted this one’s eye, and that one’s bowels. Look at this old man, shaking and limping and spitting through what few rotten teeth he has left as he rushes toward the cart with the monster on it. Wasn’t he the one whose sexual powers Ot had blighted, causing him to sob into his pillow night after night? And look at that deformed girl sticking her head through the gap at one corner and snarling as she tried to bite him. Isn’t she the one whose hands he crippled, hadn’t he confused and twisted the thoughts in her head? And look at the fat fruit vendor, with spittle and foam on her mouth and a cane in her hand. Who was it defiled her daughter in the dark of night? Him.

ng of respectable folk who were simply unable and, more to the point, unwilling to tame their rage and hatred was crowding around the cart. And why not? Why shouldn’t they spit and flail at this man who had, after all, been proven guilty? Silently and with downcast eyes he endured the people’s righteous anger. He was guilty of everything they had proven, and probably quite a bit more. Directly or indirectly, he had inflicted some evil on each of those good, hard-working people. He had caused the death of this one’s livestock and that one’s child. Another was sick because of him, and yet another was tormented by vile monsters in his sleep. He had afflicted this one’s eye, and that one’s bowels. Look at this old man, shaking and limping and spitting through what few rotten teeth he has left as he rushes toward the cart with the monster on it. Wasn’t he the one whose sexual powers Ot had blighted, causing him to sob into his pillow night after night? And look at that deformed girl sticking her head through the gap at one corner and snarling as she tried to bite him. Isn’t she the one whose hands he crippled, hadn’t he confused and twisted the thoughts in her head? And look at the fat fruit vendor, with spittle and foam on her mouth and a cane in her hand. Who was it defiled her daughter in the dark of night? Him.

He had done these and other horrible things. He has caused people to wake up at night feeling a great weight on their chest and sweat on their foreheads and palms. He had clambered over their roofs, slammed their shutters in the dead of night, tiptoed around their beds, afflicted their bowls, rotted their teeth, taken away their appetites, caused them to rave with fever, and implanted boil-like formations in their bodies.

Him and others like him.

For me, this is perhaps the best passage of any kind, fiction or nonfiction, that I have read about the belief in witchcraft. I remember when I was young and would watch a movie set in the Middle Ages. When the inevitable scene of a blood-thirsty mob arrived, I’d think, “Whew, I’m glad I didn’t have to live back then!” Yet, the psychological dynamic known as witchcraft we now call by other names—office politics, for example. This section of Jancar’s novel has cast part of my own life experience in a clearer light, dramatizing how we project our miseries onto others and blame them, even though that blame doesn’t heal our misery.

Travel can be both an exhausting and exhilarating experience, one that can push us past borders of comfort we, perhaps, had never before recognized. The unsettling immediacy of travel heightens our awareness and encourages unexpected insight, and when one is able to lean into the strange pull of another country or culture, one’s inner landscape is correspondingly altered. The earliest moments of being somewhere else also begin the process of that distant place becoming incrementally familiar, ever closer, so that what seems external travels to you sets up shop in your internal life.

Our culture lies to us (it’s an unintentional lie) with its quiet insistence on the ultimate primacy of the physical world. “How was your trip?” a friend might ask, the question posed in the past tense because that is the way the assumptions of our language are structured. Since you have returned, you are no longer there, any GPS system can prove that easily enough. But any trip’s fundamental revelations settle into your present moments. That foreign country may indeed still be over there, but now it’s inside you, too.

Writing that travels can offer a similar experience. A phrase, a sentence, a brief evocative section or even an entire work can unsettle us and take residence within. This, I think, is the essential reading experience of writing that travels: we willingly place ourselves in unfamiliar territory and brave its possible change.

*

This post has been adapted from a lecture I delivered on June 29, 2012 at the Vermont College of Fine Arts residency abroad in Skofja Loka, Slovenia.

*

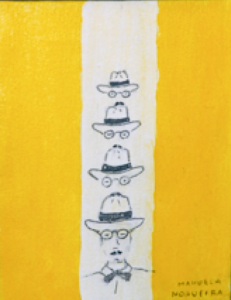

Portrait of Fernando Pessoa by Manuela Nogueira.